Creation and ordering of the universe is seen as an act of prime mercy for which all creatures sing God's glories and bear witness to God's unity and lordship. According to the Islamic teachings, God exists without a place.[5] According to the Qur'an, "No vision can grasp Him, but His grasp is over all vision. God is above all comprehension, yet is acquainted with all things" (Qur'an 6:103)[2]

God responds to those in need or distress whenever they call. Above all, God guides humanity to the right way, “the holy ways.”[5]

According to Islam there are 99 Names of God (al-asma al-husna lit. meaning: "The best names") each of which evoke a distinct attribute of God.[6][7] All these names refer to Allah, the supreme and all-comprehensive divine name.[8] Among the 99 names of God, the most famous and most frequent of these names are "the Compassionate" (al-rahman) and "the Merciful" (al-rahim).[6][7]

Islam teaches that God, as referenced in the Qur'an, is the only God and the same God worshipped by members of other Abrahamic religions such as Christianity and Judaism. (29:46).[9]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Oneness of God

Main article: Oneness of God (Islam)

Oneness of God or Tawḥīd is the act of believing and affirming that God (Arabic: Allah) is one and unique (wāḥid). The Qur'an asserts the existence of a single and absolute truth that transcends the world; a unique and indivisible being who is independent of the entire creation.[10] According to the Qur'an:[10]"Say: He is God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him." (Sura 112:1-4, Yusuf Ali)According to Vincent J. Cornell, the Qur'an also provides a monist image of God by describing the reality as a unified whole, with God being a single concept that would describe or ascribe all existing things:"God is the First and the Last, the Outward and the Inward; God is the Knower of everything (Sura 57:3)"[10] Some Muslims have however vigorously criticized interpretations that would lead to a monist view of God for what they see as blurring the distinction between the creator and the creature, and its incompatibility with the monotheism of Islam.[11]

Thy Lord is self-sufficient, full of Mercy: if it were God's will, God could destroy you, and in your place appoint whom God will as your successors, even as God raised you up from the posterity of other people." (Sura 6:133, Yusuf Ali)

The indivisibility of God implies the indivisibility of God's sovereignty which in turn leads to the conception of universe as a just and coherent moral universe rather than an existential and moral chaos (as in polytheism). Similarly the Qur'an rejects the binary modes of thinking such as the idea of duality of God by arguing that both good and evil generate from God's creative act and that the evil forces have no power to create anything. God in Islam is a universal god rather than a local, tribal or parochial one; an absolute who integrates all affirmative values and brooks no evil.[12]

Tawhid constitutes the foremost article of the Muslim profession.[13] To attribute divinity to a created entity is the only unpardonable sin mentioned in the Qur'an.[12] Muslims believe that the entirety of the Islamic teaching rests on the principle of Tawhid.[14]

[edit] God's attributes

The Qur'an refers to the attributes of God as God's “most beautiful names” (see 7:180, 17:110, 20:8, 59:24). According to Gerhard Böwering, "They are traditionally enumerated as 99 in number to which is added as the highest name (al-ism al-aʿẓam), the supreme name of God, Allāh. The locus classicus for listing the divine names in the literature of qurʾānic commentary is 17:110, “Call him Allah (the God), or call him Ar-Rahman (the Gracious); whichsoever you call upon, to him belong the most beautiful names,” and also 59:22-24, which includes a cluster of more than a dozen divine epithets."[15] The most commonly used names for god in Islam are:- The Most High (al-Ala)

- The Most Glorious (al-Aziz)

- The Ever Forgiving (al-Ghaffar)

- The Ever Providing (ar-Razzaq)

- The Ever Living (al-Hayy)

- The Self-Subsisting by Whom all Subsist (al-Qayyum)

- The Lord and Cherisher of the Worlds (Rabb al-Alameen)

- The Ultimate Truth (al-Haqq)

- The Eternal Lord (al-Baqi)

- The Sustainer (al-Muqsith)

- The Source of Peace (As-Salaam)

Furthermore, it is one of the fundamentals in Islam that God exists without a place and has no resemblance to his creations. For instance, God is not a body and there is nothing like him. In the Quran it says what mean "Nothing is like him in any way," [see Quran 42:11]. Allah is not limited to Dimensions.

[edit] Names of God

Main article: Names of God in Islam

[edit] God's omniscience

The Qur'an describes God as being fully aware of everything that happens in the universe, including private thoughts and feelings, and asserts that one can not hide anything from God:In whatever business thou mayest be, and whatever portion thou mayest be reciting from the Qur'an,- and whatever deed ye (mankind) may be doing,- We are witnesses thereof when ye are deeply engrossed therein. Nor is hidden from thy Lord (so much as) the weight of an atom on the earth or in heaven. And not the least and not the greatest of these things but are recorded in a clear record.—[10:61]

[edit] Comparative theology

Further information: Comparative theology and Abrahamic religion

Islamic theology identifies God as described in the Qur'an as the same God of Israel who covenated with Abraham.[16] Francis Edwards Peters states that the Qur'an portrays Allah as both more powerful and more remote than the God of the Hebrew Bible.[9]Islam and Judaism alike reject the Trinity of Nicene Christianity, instead teaching that God is a singular entity beside whom no one else should be worshiped. However, the identification of God both in Islam and in Christianity with the God of Abraham led to a limited amount of mutual recognition among the Abrahamic religions.[17]

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Gerhard Böwering, God and his Attributes, Encyclopedia of the Quran

- ^ a b John L. Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, Oxford University Press, 1998, p.22

- ^ John L. Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path, Oxford University Press, 1998, p.88

- ^ "Allah." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b Britannica Encyclopedia, Islam, p. 3

- ^ a b Bentley, David (September 1999). The 99 Beautiful Names for God for All the People of the Book. William Carey Library. ISBN 0-87808-299-9.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa, Allah

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel,The Tao of Islam: A Sourcebook on Gender Relationships in Islamic, SUNY Press, p.206

- ^ a b F.E. Peters, Islam, p.4, Princeton University Press, 2003

- ^ a b c Vincent J. Cornell, Encyclopedia of Religion, Vol 5, pp.3561-3562

- ^ Roger S. Gottlie (2006), p.210

- ^ a b Asma Barlas (2002), p.96

- ^ D. Gimaret, Tawhid, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ Tariq Ramadan (2005), p.203

- ^ a b Böwering, Gerhard. "God and his Attributes ." Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān.

- ^ According to Francis Edwards Peters, "The Qur'an insists, Muslims believe, and historians affirm that Muhammad and his followers worship the same God as the Jews [see Qur'an 29:46]. The Quran's Allah is the same Creator God who covenanted with Abraham".

- ^ Ludovico Marracci (1734), the confessor of Pope Innocent XI, states: William Montgomery Watt, Islam and Christianity today: A Contribution to Dialogue, Routledge, 1983, p.45

That both Mohammed and those among his followers who are reckoned orthodox, had and continue to have just and true notions of God and his attributes, appears so plain from the Koran itself and all the Muslim laws, that it would be loss of time to refute those who suppose the God of Mohammed to be different from the true God.

[edit] External links

- Allah an article by Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Allah's 99 Names, their Meanings and related audio at www.SearchTruth.com

- Some Names of Allaah

- Who is Allah?

- Allah, the unique name of God

[edit] Bibliography

- Al-Bayhaqi (1999), Allah's Names and Attributes, ISCA, ISBN 1-930409-03-6

- Hulusi, Ahmed (1999), "Allah" as introduced by Mohammed, Kitsan, 10th ed., ISBN 975-7557-41-2

- Muhaiyaddeen, M. R. Bawa (1976), Asmāʼul-Husnā: the 99 beautiful names of Allah, The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship, ISBN 0-914390-13-9

- Netton, Ian Richard (1994), Allah Transcendent: Studies in the Structure and Semiotics of Islamic Philosophy, Theology and Cosmology, Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-0287-3

This article is about the Islamic creed. For the Islamic history book, see No god but God. For other uses, see Shahada (disambiguation).

| This article is part of the series: |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Silver coin of the Mughal Emperor Akbar with inscriptions of the Islamic declaration of faith, the declaration reads: "There is none worthy of worship but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God."

- لا إله إلا الله محمد رسول الله (lā ʾilāha ʾillallāh, Muḥammad rasūlu-llāh) (in Arabic)

- There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God. (in English)

The word Shahādah is a noun stemming from the verb shahida meaning to observe, witness, or testify; when used in legal terms, shahādah is a testimony to the occurrence of events such as debt, adultery, or divorce.[2] The shahādah can also be expressed in the dual form shahādatān (= "two testifyings"), which refers to dual act of observing or seeing and then the declaration of the observation. The two acts in Islam are observing or perceiving that there is no god but God and testifying or witnessing that Muhammad is the messenger of God. In a third meaning, shahādah can mean martyrdom, the shahid (martyr) demonstrating the ultimate expression of faith.[3]

A single honest recitation of the Shahadah in Arabic is all that is required for a person to become a Muslim. This declaration, or statement of faith, is called the Kalima, literally "word". Recitation of the Shahadah, the "oath" or "testimony", is the most important of the Five Pillars of Islam for Muslims. Non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam do so by a public recitation of this creed.[4] Technically the Shi'a do not consider the Shahadah to be a separate pillar, but connect it to the Aqidah.[5] The complete Shahadah cannot be found in the Quran, but comes from hadiths.[6]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Recitation

- Arabic text: أشهد أن لا إله إلا الله و أشهد أن محمد رسول الله.

- Romanization: ʾašhadu ʾan lā ʾilāha ʾilla (A)llāh, wa ʾašhadu ʾanna Muḥammada(n) rasūlu (A)llāh

In usage the two occurrences of ašhadu ʾanna (or similar) = "I testify that" or "I bear witness that..." are very often omitted.

Shia recite the kalima as follows: "ʾAšhadu an lā ʾilāha ʾilla-llāha, wa ʾašhadu anna Muḥammad(an) ʿAbduhu wa rasūluhu wa ʾašhadu ʾanna mūlānā ʿAli-yyun wali-yyu-llāh.", and the oath now means: "I bear witness that there is no god but God, and I bear witness that Mohammad is God's servant and His Messenger and I bear witness that Ali is God's wali (representative)." The last phrase is optional to some Shia. They feel that Ali's walayat is self-evident and need not be declared.[citation needed]

[edit] History

|  | |

| A mancus / gold dinar of the king Offa of Mercia, copied from the dinars of the Abbasid Caliphate (774); probably unintentionally, it still includes the Arabic text Muhammad is the Apostle of God. | Qiblah of imam Mustansir in Fatemid masjid of Cairo showing Kalema-tut-shahadat with phrase Ali-un Wali-u(A)l-lah |

The photo above shows auxiliary Qiblah in one of pillars in the (Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo built in the Fatimid Caliphate Imam’s era of Egypt having engraved in stone the name of the 18th Imam Mustansir (1035-1094 A.D.) and the complete Kalema in the same form as above. “Lā ʾilāh-a ʾilla-llah, Muḥammad-an rasūl-ullāh, ʿAli-yyun wali-u(A)l-lah (clearly visible).”,

The Kalema in its complete Shia form also exists at the gate Bab al-Futuh built by Fatimid minister Badr al-Jamali (952-975 A.D.) at northern wall of Fatemid Cairo.

[edit] Conditions

Muslims believe that the shahadah is without value unless it is earnest. Islamic scholars have therefore developed, based on the data of the Quran and hadith, essential criteria for an expression of the shahadah to be earnest. These criteria are generally divided into seven or eight or nine individual criteria; the varying numbers and orderings are not due to disagreements about what the criteria actually are, but rather different ways of dividing them.[8]One such list of seven critical conditions of the shahadah, without which it is considered to be meaningless, are as follows:[citation needed].

- Al-`Ilm (العلم): Knowledge of the meaning of the Shahadah, its negation and affirmation.

- Al-Yaqeen (اليقين): Certainty – perfect knowledge of it that counteracts suspicion and doubt.

- Al-Ikhlaas (الإخلاص): Sincerity which negates shirk.

- Al-Sidq (الصدق): Truthfulness that permits neither falsehood nor hypocrisy.

- Al-Mahabbah (المحبة): Love of the Shahadah and its meaning, and being happy with it.

- Al-Inqiad (الانقياد): Submission to its rightful requirements, which are the duties that must be performed with sincerity to God (alone) seeking His pleasure.

- Al-Qubool (القبول): Acceptance that contradicts rejection.

- To believe in the Prophet and in whatever he said and conveyed in his message as the seal of the prophets.

- To obey him in whatever he commanded.

- To stay away from or avoid whatever he commanded Muslims not to do.

- To follow or emulate him in our ʿibādah (عبادة; worship), ʾaḫlāq (أخلاق; manners), and way of life.

- To love him more than you love yourself, your family and anything else in this world.

- To understand, practice, and promote his sunnah (habits) in the best way possible, without creating any chaos, enmity or harm.

[edit] Flags

[edit] National flag

An analysis of the calligraphy used in the flag of Saudi Arabia and derived designs is presented below:

It can be seen in the second flag that the name of Allah (الله) is written in a higher position. The name for Allah is written twice in each flag, but the first ʾalif (ا) is written after the second lām (ل) only once in the first instance of Allah in the second flag (pink), and only once in the second appearance in the flag of Saudi Arabia (green). This overwriting is also visible for the lam of rasul(u) (light blue), but only in the Saudi Arabia flag. The ligature lām + ʾalif (لا) is always written the same way in the Saudi Arabia flag, but calligraphy is changed in the case of the second لا (red) of the second flag at the left.

[edit] Jihadist flags

Further information: Black flag of jihad

Flags reported as in use in jihadism have been frequently displaying the shahada, usually on a black background, since ca. 2000. The Taliban used a white flag with the shahada inscribed in black from 1997, until 2001 as the flag of their Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.Flags showing the shahadaa, often written on a green background, have also been displayed by supporters of Hamas in rallies during the 2000s.

[edit] Turkish national anthem

The Shahadah is referenced in the eighth stanza of the Turkish national anthem which can be translated as:[edit] Shia and Sufi

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Shahada |

Sometimes أشهد أن ʾašhadu ʾan = "I witness that" is prefixed to each half of the Shahadah.

Sometimes و wa = "and" is prefixed to the first word of the second half of the Shahada.

Shī‘a Muslims add "وعليٌ وليُّ الله", meaning "and Ali is the wali (vicegerent) of God" (wa-ʿAli-yyun wali-yyu llāh).

- (Not to be confused with) shahid

- La ilaha ilallah

- Profession (religious)

- Takfir

- Takbir

- Basmala (or Bismillah)

- Kalima

- Six Kalimas

- List of Islamic terms in Arabic

- List of Christian terms in Arabic

[edit] References

- ^ "The Origin of the Sunni/Shia split in Islam". Islamfortoday.com. http://www.islamfortoday.com/shia.htm. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ^ The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Cyril Glasse, Alta Mira Press, 2001, p.416.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume IX, Klijkebrille, 1997, p.201.

- ^ Farah (1994), p.135

- ^ "If You Decide to Convert they put this their most important pilar". http://www.al-islam.org/reflectionsnewmuslim/8.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ "Shahadah". Albalagh.net. http://www.albalagh.net/kids/understanding_deen/Shahadah.shtml. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ^ "A Bilingual Papyrus Of A Protocol - Egyptian National Library Inv. No. 61, 86-96 AH / 705-715 CE". Islamic-awareness.org. 2005-12-20. http://www.islamic-awareness.org/History/Islam/Papyri/enlp1.html. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ^ "9 Point Shahadah". Islamtomorrow.com. 2002-08-06. http://www.islamtomorrow.com/9points.htm. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

Muslims believe the Quran to be verbally revealed through angel Jibrīl (Gabriel) from God to Muhammad gradually over a period of approximately twenty-three years beginning in 610 CE, when Muhammad was forty, and concluding in 632 CE, the year of his death.[1][12][13] Muslims further believe that the Qur'an was precisely memorized, recited and exactly written down by Muhammad's companions (Sahaba) after each revelation was dictated by him.[citation needed]

Shortly after Muhammad's death the Quran was compiled into a single book by order of the first Caliph Abu Bakr and at the suggestion of his future successor Umar. Hafsa, Muhammad's widow and Umar's daughter, was entrusted with that Quranic text after the second Caliph Umar died.[14] When the third Caliph Uthman began noticing slight differences in Arabic dialect he sought Hafsa's permission to use her text to be set as the standard dialect, the Quraish dialect now known as Fus'ha (Modern Standard Arabic). Before returning the text to Hafsa Uthman made several thousand copies of Abu Bakr's redaction and, to standardize the text, invalidated all other versions of the Quran. This process of formalization is known as the "Uthmanic recension".[15] The present form of the Quran text is accepted by most scholars as the original version compiled by Abu Bakr.[15][16]

Muslims regard the Quran as the main miracle of Muhammad, the proof of his prophethood[17] and the culmination of a series of divine messages that started with the messages revealed to Adam, regarded in Islam as the first prophet,[18] and continued with the Suhuf Ibrahim (Scrolls of Abraham),[19] the Tawrat (Torah or Pentateuch) of Moses,[20][21] the Zabur (Tehillim or Book of Psalms) of David,[22][23] and the Injil (Gospel) of Jesus.[24][25][26] The Quran assumes familiarity with major narratives recounted in Jewish and Christian scriptures, summarizing some, dwelling at length on others and in some cases presenting alternative accounts and interpretations of events.[27][28][29] The Quran describes itself as a book of guidance, sometimes offering detailed accounts of specific historical events, and often emphasizing the moral significance of an event over its narrative sequence.[30][31]

Contents[hide] |

Etymology and meaning

The word qurʾān appears about 70 times in the Quran itself, assuming various meanings. It is a verbal noun (maṣdar) of the Arabic verb qaraʾa (Arabic: قرأ), meaning “he read” or “he recited.” The Syriac equivalent is qeryānā, which refers to “scripture reading” or “lesson”. While most Western scholars consider the word to be derived from the Syriac, the majority of Muslim authorities hold the origin of the word is qaraʾa itself.[32] In any case, it had become an Arabic term by Muhammad's lifetime.[1] An important meaning of the word is the “act of reciting”, as reflected in an early Quranic passage: “It is for Us to collect it and to recite it (qurʾānahu)”.[33]In other verses, the word refers to “an individual passage recited [by Muhammad]”. Its liturgical context is seen in a number of passages, for example: "So when al-qurʾān is recited, listen to it and keep silent".[34] The word may also assume the meaning of a codified scripture when mentioned with other scriptures such as the Torah and Gospel.[35]

The term also has closely related synonyms that are employed throughout the Quran. Each synonym possesses its own distinct meaning, but its use may converge with that of qurʾān in certain contexts. Such terms include kitāb (“book”); āyah (“sign”); and sūrah (“scripture”). The latter two terms also denote units of revelation. In the large majority of contexts, usually with a definite article (al-), the word is referred to as the “revelation” (wahy), that which has been “sent down” (tanzīl) at intervals.[36][37] Other related words are: dhikr, meaning "remembrance," used to refer to the Quran in the sense of a reminder and warning; and hikma, meaning “wisdom”, sometimes referring to the revelation or part of it.[32][38]

The Quran has many other names. Among those found in the text itself are al-furqān (“discernment” or “criterion”), al-hudah (“"the guide”), ḏikrallāh (“the remembrance of God”), al-ḥikmah (“the wisdom”), and kalāmallāh (“the word of God”). Another term is al-kitāb (“the book”), though it is also used in the Arabic language for other scriptures, such as the Torah and the Gospels. The term muṣḥaf ("written work") is often used to refer to particular Quranic manuscripts but is also used in the Quran to identify earlier revealed books.[1]

History

Main article: History of the Quran

Prophetic era

See also: Wahy

Islamic tradition relates that Muhammad received his first revelation in the Cave of Hira during one of his isolated retreats to the mountains. Thereafter, he received revelations over a period of twenty-three years. According to hadith and Muslim history, after Muhammad emigrated to Medina and formed an independent Muslim community, he ordered a considerable number of the sahabah to recite the Quran and to learn and teach the laws, which were revealed daily. Companions who engaged in the recitation of the Quran were called Qari. Since most sahabah were unable to read or write, they were ordered to learn from the prisoners-of-war the simple writing of the time. Thus a group of sahabah gradually became literate. As it was initially spoken, the Quran was recorded on tablets, bones and the wide, flat ends of date palm fronds. Most chapters were in use amongst early Muslims since they are mentioned in numerous sayings by both Sunni and Shia sources, relating Muhammad's use of the Quran as a call to Islam, the making of prayer and the manner of recitation. However, the Quran did not exist in book form at the time of Muhammad's death in 632.[39][40]The Islamic studies scholar Welch states in the Encyclopaedia of Islam that he believes the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition at these moments may be regarded as genuine, because he was severely disturbed after these revelations. According to Welch, these seizures would have been seen by those around him as convincing evidence for the superhuman origin of Muhammad's inspirations. However, Muhammad's critics accused him of being a possessed man, a soothsayer or a magician since his experiences were similar to those claimed by such figures well known in ancient Arabia. Welch additionally states that it remains uncertain whether these experiences occurred before or after Muhammad's initial claim of prophethood.[41]

The Quran states that Muhammad was ummi,[42] interpreted as illiterate in Muslim tradition. According to Watt, the meaning of the Quranic term ummi is unscriptured rather than illiterate.

Compiling the Mus'haf

According to Shias, Sufis and scarce Sunni scholars, Ali compiled a complete version of the Quran mus'haf[1] immediately after Muhammad's death. The order of this mus'haf differed from that gathered later during Uthman's era. Despite this, Ali made no objection or resistance against standardized mus'haf, but kept his own book.[39][43]After seventy reciters were killed in the Battle of Yamama, the caliph Abu Bakr decided to collect the different chapters and verses into one volume. Thus, a group of reciters, including Zayd ibn Thabit, collected the chapters and verses and produced several hand-written copies of the complete book.[39][44]

In about 650, as Islam expanded beyond the Arabian peninsula into Persia, the Levant and North Africa, the third caliph Uthman ibn Affan ordered the preparation of an official, standardized version, to preserve the sanctity of the text (and perhaps to keep the Rashidun Empire united, see Uthman Qur'an). Five reciters from amongst the companions produced a unique text from the first volume, which had been prepared on the orders of Abu Bakr and was kept with Hafsa bint Umar. The other copies already in the hands of Muslims in other areas were collected and sent to Medina where, on orders of the Caliph, they were destroyed by burning or boiling. This remains the authoritative text of the Quran to this day.[39][45][46]

The Quran in its present form is generally considered by academic scholars to record the words spoken by Muhammad because the search for variants in Western academia has not yielded any differences of great significance. Historically, controversy over the Quran's content has rarely become an issue, although debates continue on the subject.[47][48]

Significance in Islam

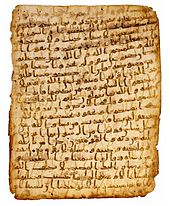

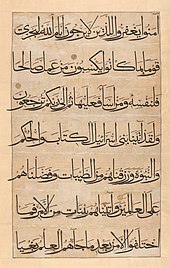

11th Century North African Quran in the British Museum

Wahy in Islamic and Quranic concept means the act of God addressing an individual, conveying a message for a greater number of recipients. The process by which the divine message comes to the heart of a messenger of God is tanzil (to send down) or nuzul (to come down). As the Quran says, "With the truth we (God) have sent it down and with the truth it has come down." It designates positive religion, the letter of the revelation dictated by the angel to the prophet. It means to cause this revelation to descend from the higher world. According to hadith, the verses were sent down in special circumstances known as asbab al-nuzul. However, in this view God himself is never the subject of coming down.[50]

The Quran frequently asserts in its text that it is divinely ordained, an assertion that Muslims believe. The Quran – often referring to its own textual nature and reflecting constantly on its assertion of divine origin – is the most meta-textual, self-referential religious text. The Quran refers to a written pre-text that records God's speech even before it was sent down.[51][52]

The issue of whether the Quran is eternal or created was one of the crucial controversies among early Muslim theologians. Mu'tazilis believe it is created while the most widespread varieties of Muslim theologians consider the Quran to be eternal and uncreated. Sufi philosophers view the question as artificial or wrongly framed.[53]

Muslims maintain the present wording of the Quranic text corresponds exactly to that revealed to Muhammad himself: as the words of God, said to be delivered to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel. Muslims consider the Quran to be a guide, a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. They argue it is not possible for a human to produce a book like the Quran, as the Quran itself maintains.

Therefore an Islamic philosopher introduces a prophetology to explain how the divine word passes into human expression. This leads to a kind of esoteric hermeneutics that seeks to comprehend the position of the prophet by mediating on the modality of his relationship not with his own time, but with the eternal source his message emanates from. This view contrasts with historical critique of western scholars who attempt to understand the prophet through his circumstances, education and type of genius.[54]

Uniqueness

See also: Quran and miracles

Muslims believe that the Quran is different from all other books in ways that are impossible for any other book to be, such that similar texts cannot be written by humans. These include both mundane and miraculous claims. The Quran itself challenges any who disagree with its divine origin to produce a text of a miraculous nature.[55]Scholars of Islam believe that its poetic form is unique and of a fashion that cannot be written by humans. They also claim it contains accurate prophecy and that no other book does.[56][57][58][59][60]

Text

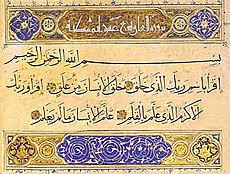

The first four verses (ayat) of Al-Alaq, the 96th sura of the Quran.

Each sura is formed from several ayat (verses), which originally means a sign or portent sent by God. The number of verses differ from chapter to chapter. An individual verse may be just a few letters or several lines. The verses are unlike the highly refined poetry of the pre-Islamic Arabs in their content and distinctive rhymes and rhythms, being more akin to the prophetic utterances marked by inspired discontinuities found in the sacred scriptures of Judaism and Christianity. The actual number of ayat has been a controversial issue among Muslim scholars since Islam's inception, some recognizing 6,000, some 6,204, some 6,219, and some 6,236, although the words in all cases are the same. The most popular edition of the Quran, which is based on the Kufa school tradition, contains 6,236 ayat.[1]

There is a crosscutting division into 30 parts of roughly equal division, ajza, each containing two units called ahzab, each of which is divided into four parts (rub 'al-ahzab). The Quran is also divided into seven approximately equal parts, manazil, for it to be recited in a week.[1]

The Quranic text seems to have no beginning, middle, or end, its nonlinear structure being akin to a web or net.[1] The textual arrangement is sometimes considered to have lack of continuity, absence of any chronological or thematic order, and presence of repetition.[63][64]

Fourteen different Arabic letters form 14 different sets of “Quranic Initials” (the "Muqatta'at", such as A.L.M. of 2:1) and prefix 29 suras in the Quran. The meaning and interpretation of these initials is considered unknown to most Muslims.

In 1974, Egyptian biochemist Rashad Khalifa claimed to have discovered a mathematical code based on the number 19,[65] which is mentioned in Sura 74:30[66] of the Quran. This code only manifests itself in a version of Quran that Khalifa published himself and which differs from the one accepted by most Muslims. It is the basis for the beliefs of United Submitters International, a religious group that Khalifa founded.

Content

Main articles: Justice in the Quran and Quran and science

See also: Legends and the Quran

The Quranic verses contain general exhortations regarding right and wrong and the nature of revelation.Historical events are related to outline general moral lessons.

Verses pertaining to natural phenomena have been interpreted by Muslims as an indication of the authenticity of the Quranic message.

Literary structure

The Quran's message is conveyed with various literary structures and devices. In the original Arabic, the chapters and verses employ phonetic and thematic structures that assist the audience's efforts to recall the message of the text. Some[citation needed] use the Quran as a standard by which other Arabic literature is measured. Muslims[who?] assert (according to the Quran itself) that the Quranic content and style is inimitable.[67]Richard Gottheil and Siegmund Fränkel in the Jewish Encyclopedia write that the oldest portions of the Quran reflect significant excitement in their language, through short and abrupt sentences and sudden transitions. The Quran nonetheless carefully maintains the rhymed form, like the oracles. Some later portions also preserve this form but also in a style where the movement is calm and the style expository.[68][verification needed]

Michael Sells, citing the work of the critic Norman O. Brown, acknowledges Brown's observation that the seeming "disorganization" of Quranic literary expression – its "scattered or fragmented mode of composition," in Sells's phrase – is in fact a literary device capable of delivering "profound effects – as if the intensity of the prophetic message were shattering the vehicle of human language in which it was being communicated."[69][70] Sells also addresses the much-discussed "repetitiveness" of the Quran, seeing this, too, as a literary device.

Interpretation and meanings

Tafsir

Main article: Tafsir

The Quran has sparked a huge body of commentary and explication (tafsir), aimed at explaining the "meanings of the Quranic verses, clarifying their import and finding out their significance."[71]Tafsir is one of the earliest academic activities of Muslims. According to the Quran, Muhammad was the first person who described the meanings of verses for early Muslims.[72] Other early exegetes included a few Companions of Muhammad, like Ali ibn Abi Talib, Abdullah ibn Abbas, Abdullah ibn Umar and Ubayy ibn Kab. Exegesis in those days was confined to the explanation of literary aspects of the verse, the background of its revelation and, occasionally, interpretation of one verse with the help of the other. If the verse was about a historical event, then sometimes a few traditions (hadith) of Muhammad were narrated to make its meaning clear.[73]

Because the Quran is spoken in classical Arabic, many of the later converts to Islam (mostly non-Arabs) did not always understand the Quranic Arabic, they did not catch allusions that were clear to early Muslims fluent in Arabic and they were concerned with reconciling apparent conflict of themes in the Quran. Commentators erudite in Arabic explained the allusions, and perhaps most importantly, explained which Quranic verses had been revealed early in Muhammad's prophetic career, as being appropriate to the very earliest Muslim community, and which had been revealed later, canceling out or "abrogating" (nasikh) the earlier text (mansukh).[74][75][76] Other scholars however maintain that no abrogation has taken place in the Qur'an[77]

Ta'wil

Main article: Esoteric interpretation of the Quran

See also: Quranic hermeneutics and Exegesis

Ja'far Kashfi defines ta'wil as 'to lead back or to bring something back to its origin or archetype'. It is a science whose pivot is a spiritual direction and a divine inspiration, while the tafsir is the literal exegesis of the letter; its pivot is the canonical Islamic sciences.[78] Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei says that according to the popular explanation among the later exegetes, ta'wil indicates the particular meaning a verse is directed towards. The meaning of revelation (tanzil), as opposed to ta'wil, is clear in its accordance to the obvious meaning of the words as they were revealed. But this explanation has become so widespread that, at present, it has become the primary meaning of ta'wil, which originally meant "to return" or "the returning place". In Tabatabaei's view, what has been rightly called ta'wil, or hermeneutic interpretation of the Quran, is not concerned simply with the denotation of words. Rather, it is concerned with certain truths and realities that transcend the comprehension of the common run of men; yet it is from these truths and realities that the principles of doctrine and the practical injunctions of the Quran issue forth. Interpretation is not the meaning of the verse; rather it transpires through that meaning – a special sort of transpiration. There is a spiritual reality, which is the main objective of ordaining a law, or the basic aim in describing a divine attribute—and there is an actual significance a Quranic story refers to.[79][80]However Shia and Sufism (on the one hand) and Sunni (on the other) have completely different positions on the legitimacy of ta'wil. A verse in the Quran[81] addresses this issue, but Shia and Sunni disagree on how it should be read. According to Shia, those who are firmly rooted in knowledge like the Prophet and the imams know the secrets of the Quran, while Sunnis believe that only God knows. According to Tabatabaei, the statement "none knows its interpretation except Allah" remains valid, without any opposing or qualifying clause. Therefore, so far as this verse is concerned, the knowledge of the Quran's interpretation is reserved for God. But Tabatabaei uses other verses and concludes that those who are purified by God know the interpretation of the Quran to a certain extent.[80]

The most ancient spiritual commentary on the Quran consists of the teachings the Shia Imams propounded in conversations with their disciples. It was the principles of their spiritual hermeneutics that were subsequently brought together by the Sufis. These texts are narrated by Imam Ali and Ja'far al-Sadiq, Shia and Sunni Sufis.[82]

As Corbin narrates from Shia sources, Ali himself gives this testimony:

Not a single verse of the Quran descended upon (was revealed to) the Messenger of God, which he did not proceed to dictate to me and make me recite. I would write it with my own hand, and he would instruct me as to its tafsir (the literal explanation) and the ta'wil (the spiritual exegesis), the nasikh (the verse that abrogates) and the mansukh (the abrogated verse), the muhkam (without ambiguity) and the mutashabih (ambiguous), the particular and the general...[83]According to Tabatabaei, there are acceptable and unacceptable esoteric interpretations. Acceptable ta'wil refers to the meaning of a verse beyond its literal meaning; rather the implicit meaning, which ultimately is known only to God and can't be comprehended directly through human thought alone. The verses in question here refer to the human qualities of coming, going, sitting, satisfaction, anger, and sorrow, which are apparently attributed to God. Unacceptable ta'wil is where one "transfers" the apparent meaning of a verse to a different meaning by means of a proof; this method is not without obvious inconsistencies. Although this unacceptable ta'wil has gained considerable acceptance, it is incorrect and cannot be applied to the Quranic verses. The correct interpretation is that reality a verse refers to. It is found in all verses, the decisive and the ambiguous alike; it is not a sort of a meaning of the word; it is a fact that is too sublime for words. God has dressed them with words to bring them a bit nearer to our minds; in this respect they are like proverbs that are used to create a picture in the mind, and thus help the hearer to clearly grasp the intended idea.[80][84]

Therefore Sufi spiritual interpretations are usually accepted by Islamic scholars as authentic, as long as certain conditions are met.[85] In Sufi history, these interpretations were sometimes considered religious innovations (bid'ah), as Salafis believe today. However, ta'wil is extremely controversial even amongst Shia. For example, when Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini, the leader of Islamic revolution, gave some lectures about Sura al-Fatiha in December 1979 and January 1980, protests forced him to suspend them before he could continue beyond the first two verses of the surah.[86]

Levels of meaning

Unlike the Salafis and Zahiri, Shias and Sufis as well as some Muslim philosophers believe the meaning of the Quran is not restricted to the literal aspect.[87] For them, it is an essential idea that the Quran also has inward aspects. Henry Corbin narrates a hadith that goes back to Muhammad:"The Qur'an possesses an external appearance and a hidden depth, an exoteric meaning and an esoteric meaning. This esoteric meaning in turn conceals an esoteric meaning (this depth possesses a depth, after the image of the celestial Spheres, which are enclosed within each other). So it goes on for seven esoteric meanings (seven depths of hidden depth)."[87]According to this view, it has also become evident that the inner meaning of the Quran does not eradicate or invalidate its outward meaning. Rather, it is like the soul, which gives life to the body.[88] Corbin considers the Quran to play a part in Islamic philosophy, because gnosiology itself goes hand in hand with prophetology.[89]

Commentaries dealing with the zahir (outward aspects) of the text are called tafsir, and hermeneutic and esoteric commentaries dealing with the batin are called ta'wil (“interpretation” or “explanation”), which involves taking the text back to its beginning. Commentators with an esoteric slant believe that the ultimate meaning of the Quran is known only to God.[1] In contrast, Quranic literalism, followed by Salafis and Zahiris, is the belief that the Quran should only be taken at its apparent meaning.

Translations

Main article: Quran translations

See also: List of translations of the Quran

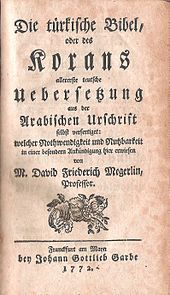

The first Quran to be translated into a European vernacular language: L'Alcoran de Mahomet, André du Ryer, 1647.

The first complete translation of the Quran was completed in 884 CE in Alwar (Sindh, India now Pakistan) by the orders of Abdullah bin Umar bin Abdul Aziz on the request of the Hindu Raja Mehruk.[92]

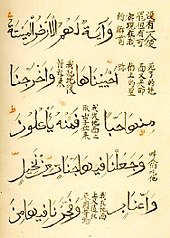

Nevertheless, the Quran has been translated into most African, Asian and European languages.[91] The first translator of the Quran was Salman the Persian, who translated sura Al-Fatiha into Persian during the 7th century.[93] The first complete translation of Quran was into Persian during the reign of Samanids in the 9th century. Islamic tradition holds that translations were made for Emperor Negus of Abyssinia and Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, as both received letters by Muhammad containing verses from the Quran.[91] In early centuries, the permissibility of translations was not an issue, but whether one could use translations in prayer.

Verses 33 and 34 of sura Ya-Seen in this Chinese translation of the Quran.

Robert of Ketton's 1143 translation of the Quran for Peter the Venerable, Lex Mahumet pseudoprophete, was the first into a Western language (Latin).[95] Alexander Ross offered the first English version in 1649, from the French translation of L'Alcoran de Mahomet (1647) by Andre du Ryer. In 1734, George Sale produced the first scholarly translation of the Quran into English; another was produced by Richard Bell in 1937, and yet another by Arthur John Arberry in 1955. All these translators were non-Muslims. There have been numerous translations by Muslims.

The English translators have sometimes favored archaic English words and constructions over their more modern or conventional equivalents; for example, two widely read translators, A. Yusuf Ali and M. Marmaduke Pickthall, use the plural and singular "ye" and "thou" instead of the more common "you".[96]

Literary usage

In addition to and largely independent of the division into suras, there are various ways of dividing the Quran into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading, recitation and memorization. The thirty ajza can be used to read through the entire Quran in a week or a month. Some of these parts are known by names and these names are the first few words by which the juz' starts. A juz' is sometimes further divided into two ahzab, and each hizb subdivided into four rub 'al-ahzab. A different structure is provided by the ruku'at, semantical units resembling paragraphs and comprising roughly ten ayat each. Some also divide the Quran into seven manazil to facilitate complete recitation in a week.Recitation

| “ | ...and recite the Quran in slow, measured rhythmic tones. | ” |

To perform salat (prayer), a mandatory obligation in Islam, a Muslim is required to learn at least some sura of the Quran (typically starting with the first one, al-Fatiha, known as the "seven oft-repeated verses," and then moving on to the shorter ones at the end). Until one has learned al-Fatiha, a Muslim can only say phrases like "praise be to God" during the salat.

Quran with colour-coded tajwid rules.

Schools of recitation

Main article: Qira'at

Page of a 13th century Quran, showing Sura 33: 73

- It must match the rasm, letter for letter.

- It must conform with the syntactic rules of the Arabic language.

- It must have a continuous isnad to Muhammad through tawatur, meaning that it has to be related by a large group of people to another down the isnad chain.

The more widely used narrations are those of Hafs (حفص عن عاصم), Warsh (ورش عن نافع), Qaloon (قالون عن نافع) and Al-Duri according to Abu `Amr (الدوري عن أبي عمرو). Muslims firmly believe that all canonical recitations were recited by Muhammad himself, citing the respective isnad chain of narration, and accept them as valid for worshipping and as a reference for rules of Sharia. The uncanonical recitations are called "explanatory" for their role in giving a different perspective for a given verse or ayah. Today several dozen persons hold the title "Memorizer of the Ten Recitations."

The presence of these different recitations is attributed to many hadith. Malik Ibn Anas has reported:[99]

- Abd al-Rahman Ibn Abd al-Qari narrated: "Umar Ibn Khattab said before me: I heard Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam reading Surah Furqan in a different way from the one I used to read it, and the Prophet (sws) himself had read out this surah to me. Consequently, as soon as I heard him, I wanted to get hold of him. However, I gave him respite until he had finished the prayer. Then I got hold of his cloak and dragged him to the Prophet (sws). I said to him: "I have heard this person [Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam] reading Surah Furqan in a different way from the one you had read it out to me." The Prophet (sws) said: "Leave him alone [O 'Umar]." Then he said to Hisham: "Read [it]." [Umar said:] "He read it out in the same way as he had done before me." [At this,] the Prophet (sws) said: "It was revealed thus." Then the Prophet (sws) asked me to read it out. So I read it out. [At this], he said: "It was revealed thus; this Quran has been revealed in Seven Ahruf. You can read it in any of them you find easy from among them.

- "And to me the best opinion in this regard is that of the people who say that this hadith is from among matters of mutashabihat, the meaning of which cannot be understood."

- Abu Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami reports, "the reading of Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Zayd ibn Thabit and that of all the Muhajirun and the Ansar was the same. They read the Quran according to the Qira'at al-'ammah. This is the same reading the Prophet (sws) read twice to Gabriel in the year of his death. Zayd ibn Thabit was also present in this reading [called] the 'Ardah-i akhirah. It was this very reading that he taught the Quran to people till his death".[102]

- Ibn Sirin writes, "the reading on which the Quran was read out to the prophet in the year of his death is the same according to which people are reading the Quran today".[103]

However, the identification of the recitation of Hafss as the Qira'at al-'ammah is somewhat problematic when that was the recitation of the people of Kufa in Iraq, and there is better reason to identify the recitation of the reciters of Madinah as the dominant recitation. The reciter of Madinah was Nafi' and Imam Malik remarked "The recitation of Nafi' is Sunnah."

AZ [however] says that the people of El-Hijaz and Hudhayl, and the people of Makkah and Al-Madinah, to not pronounce hamzah [at all]: and 'Isa Ibn-'Omar says, Tamim pronounce hamzah, and the people of Al-Hijaz, in cases of necessity, [in poetry,] do so.[104]

Writing and printing

Page from a Quran ('Umar-i Aqta'). Iran, Afghanistan, Timurid dynasty, circa 1400. Opaque watercolor, ink and gold on paper Muqaqqaq script. 170 x 109cm (66 15/16 x 42 15/16in). Historical region: Uzbekistan.

Qurans are produced in many different sizes. Most are of a reasonable book size, but there exist extremely large Qurans (usually for display purposes) and very small Qurans (sometimes given as gifts).

Before printing was widely adopted in the 19th century, the Quran was transmitted in manuscript books made by copyists and calligraphers. Short extracts from the Quran were printed in the medieval period from carved wooden blocks, one block per page; a technique already widely used in China. However there are no records of complete Qurans produced in this way, which would have involved a very large investment.[105] Mass-produced less expensive versions of the Quran were produced from the 19th century by lithography, which allowed reproduction of the fine calligraphy of hand-made versions.[106]

The first and last chapters of the Quran together written in the Shikastah style.

It is extremely difficult to render the full Quran, with all the points, in computer code, such as Unicode. The Internet Sacred Text Archive makes computer files of the Quran freely available both as images[109] and in a temporary Unicode version.[110] Various designers and software firms have attempted to develop computer fonts that can adequately render the Quran.[111]

Since Muslim tradition felt that directly portraying sacred figures and events might lead to idolatry, it was considered wrong to decorate the Quran with pictures (as was often done for Christian texts, for example). Muslims instead lavished love and care upon the sacred text itself. Arabic is written in many scripts, some of which are complex and beautiful. Arabic calligraphy is a highly honored art, much like Chinese calligraphy. Muslims also decorated their Qurans with abstract figures (arabesques), colored inks, and gold leaf. Pages from some of these antique Qurans are displayed throughout this article.

Relationship with other literature

Torah, Hebrew Bible and New Testament

See also: Biblical narratives and the Quran and Tawrat

| “ | It is He Who sent down to thee (step by step), in truth, the Book, confirming what went before it; and He sent down the Law (of Moses) and the Gospel (of Jesus) before this, as a guide to mankind, and He sent down the criterion (of judgment between right and wrong).[112] | ” |

According to Sahih Bukhari, the Quran was recited among Levantines and Iraqis, and discussed by Christians and Jews before it was standardized.[114] Its language was similar to the Syriac language. The Quran recounts stories of many of the people and events recounted in Jewish and Christian sacred books (Tanakh, Bible) and devotional literature (Apocrypha, Midrash), although it differs in many details. Adam, Enoch, Noah, Eber, Shelah, Abraham, Lot, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Job, Jethro, David, Solomon, Elijah, Elisha, Jonah, Aaron, Moses, Zechariah, John the Baptist, and Jesus are mentioned in the Quran as prophets of God (see Prophets of Islam). In fact, Jesus is mentioned more often in the Quran than Muhammad. At the same time, Mary is also mentioned in the Quran more than the New Testament.[115] Muslims believe the common elements or resemblances between the Bible and other Jewish and Christian writings and Islamic dispensations is due to their common divine source, and that the original Christian or Jewish texts were authentic divine revelations given to prophets.

Similarities with Christian apocrypha

The Quran has been noted to have certain narratives similarities to the Diatessaron, Protoevangelium of James, Infancy Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and the Arabic Infancy Gospel.[116][117][118] One scholar has suggested that the Diatessaron, as a gospel harmony, may have led to the conception that the Christian Gospel is one text.[119]Arab writing

Muhaqqaq script

Wadad Kadi, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at University of Chicago and Mustansir Mir, Professor of Islamic studies at Youngstown State University state that:[121]

Although Arabic, as a language and a literary tradition, was quite well developed by the time of Muhammad's prophetic activity, it was only after the emergence of Islam, with its founding scripture in Arabic, that the language reached its utmost capacity of expression, and the literature its highest point of complexity and sophistication. Indeed, it probably is no exaggeration to say that the Quran was one of the most conspicuous forces in the making of classical and post-classical Arabic literature.

The main areas in which the Qur'an exerted noticeable influence on Arabic literature are diction and themes; other areas are related to the literary aspects of the Qur'an particularly oaths (q.v.), metaphors, motifs, and symbols. As far as diction is concerned, one could say that Qur'anic words, idioms, and expressions, especially "loaded" and formulaic phrases, appear in practically all genres of literature and in such abundance that it is simply impossible to compile a full record of them. For not only did the Qur'an create an entirely new linguistic corpus to express its message, it also endowed old, pre-Islamic words with new meanings and it is these meanings that took root in the language and subsequently in the literature...

Culture

Arabic Quran with Persian translation.

Arabic Quran with Persian translation from the Ilkhanid Era.

Based on tradition and a literal interpretation of sura 56:77–79: "That this is indeed a Quran Most Honourable, In a Book well-guarded, Which none shall touch but those who are clean.", many scholars believe that a Muslim must perform a ritual cleansing with water (wudu) before touching a copy of the Quran, or mus'haf, although this view is ubiquitous.

Quran desecration means mishandling the Quran by defiling or dismembering it. Muslims believe they should always treat the book with reverence, and are forbidden, for instance, to pulp, recycle, or simply discard worn-out copies of the text. Respect for the written text of the Quran is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims. They believe that intentionally insulting the Quran is a form of blasphemy.

The text of the Quran has become readily accessible over the internet, in Arabic as well as numerous translations in other languages. It can be downloaded and searched both word-by-word and with Boolean algebra. Photos of ancient manuscripts and illustrations of Quranic art can be witnessed. However, there are still limits to searching the Arabic text of the Quran.[124]

See also

| Previous sura: ' | The Qur'an - Sura | Next sura: — |

| Arabic text | ||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 | ||

Notes

^/qurˈʔaːn/ : Actual pronunciation in Literary Arabic varies regionally. The first vowel varies from [o] to [ʊ] to [u], while the second vowel varies from [æ] to [a] to [ɑ]. Example, in Egypt: [qorˤˈʔɑːn], in Central East Arabia: [qʊrˈʔæːn].- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qurʾān". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-68890/Quran. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ a b Watton, Victor, (1993), A student's approach to world religions:Islam, Hodder & Stoughton, pg 1. ISBN 978-0-340-58795-9

- ^ Shaikh, Khalid Mahmood (1999). A study of the Qur'an & its teachings. IQRA International Educational Foundation. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-56316-118-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=wjNneGwYhUIC&lpg=PA71&dq=%22is%20the%20last%20and%20final%20testament.%22&pg=PA44#v=onepage&q=%22is%20the%20last%20and%20final%20testament.%22&f=false.

- ^ Alan Jones, The Koran, London 1994, ISBN 978-1-84212-609-7, opening page.

- ^ Arthur Arberry, The Koran Interpreted, London 1956, ISBN 978-0-684-82507-6, p. x.

- ^ Chejne, A. (1969) The Arabic Language: Its Role in History, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

- ^ Nelson, K. (1985) The Art of Reciting the Quran, University of Texas Press, Austin

- ^ Speicher, K. (1997) in: Edzard, L., and Szyska, C. (eds.) Encounters of Words and Texts: Intercultural Studies in Honor of Stefan Wild. Georg Olms, Hildesheim, pp. 43–66.

- ^ Taji-Farouki, S. (ed.) (2004) Modern Muslim Intellectuals and the Quran, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- ^ Kermani, Naved. Poetry and Language. In: The Blackwell Companion to the Qur'an (2006). ed: Andrew Rippin. Blackwell Publishing

- ^ What Everyone Should Know About the Qur'an Ahmed Al-Laithy

- ^ a b c Living Religions: An Encyclopaedia of the World's Faiths, Mary Pat Fisher, 1997, page 338, I.B. Tauris Publishers.

- ^ a b Quran 17:106

- ^ http://www.quran.net/quran/PreservationOfTheQuran.htm

- ^ a b "CRCC: Center For Muslim-Jewish Engagement: Resources: Religious Texts". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. http://web.archive.org/web/20110107135721/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/engagement/resources/texts/muslim/hadith/bukhari/061.sbt.html#006.061.510. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ See:

- William Montgomery Watt in The Cambridge History of Islam, p.32

- Richard Bell, William Montgomery Watt, 'introduction to the Qurʼān', p.51

- F. E. Peters (1991), pp.3–5: “Few have failed to be convinced that … the Quran is … the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation.”

- ^ Peters (2003), pp.12 and 13[Full citation needed]

- ^ Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Prophets in the Quran: an introduction to the Quran and Muslim exegesis. Continuum. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8264-4956-6.

- ^ Quran 87:18–19

- ^ Quran 3:3

- ^ Quran 5:44

- ^ Quran 4:163

- ^ Quran 17:55

- ^ Quran 5:46

- ^ Quran 5:110

- ^ Quran 57:27

- ^ Quran 3:84

- ^ Quran 4:136

- ^ “The Quran assumes the reader is familiar with the traditions of the ancestors since the age of the Patriarchs, not necessarily in the version of the ‘Children of Israel’ as described in the Bible but also in the version of the ‘Children of Ismail’ as recounted orally, interspersed with polytheist elements, at the time of Muhammad. The term jahiliya (ignorance), used to speak of the pre-Islamic epoch, does not imply that the Arabs were not familiar with their traditional roots but that their knowledge of ethical and spiritual values had been lost.” Exegesis of Bible and Qur'an, H. Krausen. Webcitation.org[unreliable source]

- ^ Nasr (2003), p.42[Full citation needed]

- ^ Quran 2:67–76

- ^ a b “Ķur'an, al-”, Encyclopedia of Islam Online.

- ^ Quran 75:17

- ^ Quran 7:204

- ^ See “Ķur'an, al-”, Encyclopedia of Islam Online and [Quran 9:111]

- ^ Quran 20:2 cf.

- ^ Quran 25:32 cf.

- ^ According to Welch in the Encyclopedia of Islam, the verses pertaining to the usage of the word hikma should probably be interpreted in the light of IV, 105, where it is said that “Muhammad is to judge (tahkum) mankind on the basis of the Book sent down to him.”

- ^ a b c d *Tabatabaee, 1988, chapter 5[Full citation needed]

- ^ See:

- William Montgomery Watt in The Cambridge History of Islam, p.32

- Richard Bell, William Montgomery Watt, Introduction to the Qurʼān, p.51

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam online, Muhammad article

- ^ Quran 7:157

- ^ See:

- Observations on Early Qur'an Manuscripts in San'a

- The Qur'an as Text, ed. Wild, Brill, 1996 ISBN 978-90-04-10344-3

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 6:60:201

- ^ Mohamad K. Yusuff, Zayd ibn Thabit and the Glorious Qur'an

- ^ The Koran; A Very Short Introduction, Michael Cook. Oxford University Press, pp. 117–124

- ^ Arthur Jeffery and St. Clair-Tisdal et al,Edited by Ibn Warraq, Summarised by Sharon Morad, Leeds. "The Origins of the Koran: Classic Essays on Islam's Holy Book". http://debate.org.uk/topics/books/origins-koran.html. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ^ *F. E. Peters (1991), pp.3–5: "Few have failed to be convinced that the Quran is the words of Muhammad, perhaps even dictated by him after their recitation."

- ^ Quran 2:23–4

- ^ See:

- Corbin (1993), p.12[Full citation needed]

- Wild (1996), pp. 137, 138, 141 and 147[Full citation needed]

- Quran 2:97

- Quran 17:105

- ^ Wild (1996), pp. 140

- ^ Quran 43:3

- ^ Corbin (1993), p.10

- ^ Corbin (1993), pp .10 and 11

- ^ [Quran 17:88]

- ^ [Quran 2:23]

- ^ [Quran 10:38]

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an – Miracles

- ^ Ahmad Dallal, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Qur'an and science

- ^ Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an – Byzantines

- ^ Arabic: بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم, transliterated as: bismi-llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi.

- ^ See:

- “Kur`an, al-”, Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- Allen (2000) p. 53

- ^ Samuel Pepys: "One feels it difficult to see how any mortal ever could consider this Koran as a Book written in Heaven, too good for the Earth; as a well-written book, or indeed as a book at all; and not a bewildered rhapsody; written, so far as writing goes, as badly as almost any book ever was!" http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/display.php?table=review&id=21

- ^ "The final process of collection and codification of the Quran text was guided by one over-arching principle: God's words must not in any way be distorted or sullied by human intervention. For this reason, no serious attempt, apparently, was made to edit the numerous revelations, organize them into thematic units, or present them in chronological order.... This has given rise in the past to a great deal of criticism by European and American scholars of Islam, who find the Quran disorganized, repetitive, and very difficult to read." Approaches to the Asian Classics, Irene Blomm, William Theodore De Bary, Columbia University Press, 1990, p. 65

- ^ Rashad Khalifa, Quran: Visual Presentation of the Miracle, Islamic Productions International, 1982. ISBN 978-0-934894-30-2

- ^ Quran 74:30 Prophecies Made in the Quran that Have Already Come True]

- ^ Issa Boullata, "Literary Structure of Quran," Encyclopedia of the Qurʾān, vol.3 p.192, 204

- ^ Jewishencyclopedia.com – Körner, Moses B. Eliezer

- ^ Michael Sells, Approaching the Qur'ān (White Cloud Press, 1999)

- ^ Norman O. Brown, "The Apocalypse of Islam." Social Text 3:8 (1983–1984)

- ^ Preface of Al'-Mizan, reference is to Allameh Tabatabaei[dead link]

- ^ Quran 2:151

- ^ Tafseer Al-Mizan[dead link]

- ^ How can there be abrogation in the Quran?

- ^ Are the verses of the Qur'an Abrogated and/or Subtituted?

- ^ Islam Review – Presented by The Pen vs. the Sword Featured Articles ... Islam: the Facade, the Facts The rosy picture some Muslims are painting about their religion, and the truth they try to hide

- ^ Islahi, Amin Ahsan (in Urdu (tr: English)). Tadabbur-i-Qur'an (Pondering over the Qur'an). http://www.monthly-renaissance.com/issue/content.aspx?id=426. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Corbin (1993), p.9

- ^ Tabataba'I, Tafsir Al-Mizan, The Principles of Interpretation of the Quran[dead link]

- ^ a b c Tabataba'I, Tafsir Al-Mizan, Topic: Decisive and Ambiguous verses and "ta'wil"[dead link]

- ^ Quran 3:7

- ^ Corbin (1993), pp.7 and 8

- ^ Corbin (1993), p.46

- ما نَزلت على رسول الله صلى الله عليه وآله وسلم آية من القرآن إلاّ أقرأنيها وأملاها عليَّ فكتبتها بخطي ، وعلمني تأويلها وتفسيرها، وناسخها ومنسوخها ، ومحكمها ومتشابهها ، وخاصّها وعامّها ، ودعا الله لي أن يعطيني فهمها وحفظها فما نسيتُ آية من كتاب الله تعالى ولا علماً أملاه عليَّ وكتبته منذ دعا الله لي بما دعا ، وما ترك رسول الله علماً علّمه الله من حلال ولا حرام ، ولا أمرٍ ولا نهي كان أو يكون.. إلاّ علّمنيه وحفظته، ولم أنسَ حرفاً واحداً منه

- ^ Tabatabaee (1988), pp. 37–45

- ^ Sufi Tafsir and Isma'ili Ta'wil

- ^ Algar, Hamid (June 2003), The Fusion of the Gnostic and the Political in the Personality and Life of Imam Khomeini (R.A.)

- ^ a b Corbin (1993), p.7

- ^ Tabatabaee, Tafsir Al-Mizan[dead link]

- ^ Corbin (1993), p.13

- ^ Aslan, Reza (20 November 2008). "How To Read the Quran". Slate. http://www.slate.com/id/2204849/?from=rss. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d Fatani, Afnan (2006). "Translation and the Qur'an". In Leaman, Oliver. The Qur'an: an encyclopedia. Great Britain: Routeledge. pp. 657–669.

- ^ Monthlycrescent.com

- ^ An-Nawawi, Al-Majmu', (Cairo, Matbacat at-'Tadamun n.d.), 380.

- ^ "More than 300 publishers visit Quran exhibition in Iran". Hürriyet Daily News and Economic Review. 12 August 2010. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/n.php?n=more-than-300-publishers-visit-koran-exhibition-in-iran-2010-08-12

- ^ Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2002. p. 42.

- ^ "Surah 3 – Read Quran Online". http://readquranonline.info/surah003.html. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ Sonn, Tamara (2006). "Art and the Qur'an". In Leaman, Oliver. The Qur'an: an encyclopedia. Great Britain: Routeledge. pp. 71–81.

- ^ Navid Kermani, Das ästhetische Erleben des Koran. Munich (1999)

- ^ Malik Ibn Anas, Muwatta, vol. 1 (Egypt: Dar Ahya al-Turath, n.d.), 201, (no. 473).

- ^ Suyuti, Tanwir al-Hawalik, 2nd ed. (Beirut: Dar al-Jayl, 1993), 199.

- ^ a b Javed Ahmad Ghamidi. Mizan, Principles of Understanding the Qur'an, Al-Mawrid

- ^ Zarkashi, al-Burhan fi Ulum al-Quran, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1980), 237.

- ^ Suyuti, al-Itqan fi Ulum al-Quran, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Baydar: Manshurat al-Radi, 1343 AH), 177.

- ^ E. W. Lane, Arabic–English Lexicon

- ^ Muslim Printing Before Gutenberg

- ^ Peter G. Riddell, Tony Street, Anthony Hearle Johns, Islam: essays on scripture, thought, and society : a festschrift in honour of Anthony H. Johns, pp. 170–174, BRILL, 1997, ISBN 978-90-04-10692-5, 9789004106925

- ^ Suraiya Faroqhi, Subjects of the Sultan: culture and daily life in the Ottoman Empire, pp, 134–136, I.B.Tauris, 2005, ISBN 978-1-85043-760-4, 9781850437604;The Encyclopaedia of Islam: Fascicules 111–112 : Masrah Mawlid, Clifford Edmund Bosworth

- ^ The Qur'an in Manuscript and Print. "The Qur'anic Script". http://www.islamworld.net/UUQ/3.txt. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Article by A. Yusuf Ali. "The Holy Qur'an". http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/quran/index.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Unicode Qur'an. "Sacred-texts". http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/uq/. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ Mishafi Font. "Award-winning calligraphic typeface". http://www.diwan.com/mishafi/main.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ 3:3 نزل عليك الكتاب بالحق مصدقا لما بين يديه وانزل التوراة والانجيل

- ^ Quran 2:285

- ^ USC.edu[dead link]

- ^ Esposito, John L. The Future of Islam. Oxford University Press US, 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-516521-0 p. 40

- ^ Christian Lore and the Arabic Qur'an by Signey Griffith, p.112, in The Qurʼān in its historical context, Gabriel Said Reynolds, ed. Psychology Press, 2008

- ^ Qur'an-Bible Comparison: A Topical Study of the Two Most Influential and Respectful Books in Western and Middle Eastern Civilizations by Ami Ben-Chanan, p. 197–198, Trafford Publishing, 2011

- ^ New Catholic Encyclopaedia, 1967, The Catholic University of America, Washington D C, Vol. VII, p.677

- ^ "On pre-Islamic Christian strophic poetical texts in the Koran" by Ibn Rawandi, found in What the Koran Really Says: Language, Text, and Commentary, Ibn Warraq, Prometheus Books, ed. ISBN 978-1-57392-945-5

- ^ Leaman, Oliver (2006). "Cyberspace and the Qur'an". In Leaman, Oliver. The Qur'an: an encyclopedia. Great Britain: Routeledge. pp. 130–135.

- ^ Wadad Kadi and Mustansir Mir, Literature and the Quran, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, vol. 3, pp. 213, 216

- ^ Mahfouz (2006), p.35

- ^ Kugle (2006), p.47; Esposito (2000a), p.275

- ^ Rippin, Andrew (2006). "Cyberspace and the Qur'an". In Leaman, Oliver. The Qur'an: an encyclopedia. Great Britain: Routeledge. pp. 159–163.

References

- Rahman, Fazlur (2009) [1989]. Major Themes of the Qur'an (Second ed.). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70286-5.

- Allen, Roger (2000). An Introduction to Arabic literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77657-8.

- Corbin, Henry (1993 (original French 1964)). History of Islamic Philosophy, Translated by Liadain Sherrard, Philip Sherrard. London; Kegan Paul International in association with Islamic Publications for The Institute of Ismaili Studies. ISBN 978-0-7103-0416-2.

- Esposito, John; Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad (2000). Muslims on the Americanization Path?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513526-8.

- Kugle, Scott Alan (2006). Rebel Between Spirit And Law: Ahmad Zarruq, Sainthood, And Authority in Islam. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34711-4.

- Mahfouz, Tarek (2006). Speak Arabic Instantly. Lulu Press, Inc.. ISBN 978-1-84728-900-1.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2003). Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 978-0-06-050714-5.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qurʾān". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-68890/Quran.

- Peters, Francis E. (2003). The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12373-8.

- Peters, F. E. (1991). "The Quest of the Historical Muhammad". International Journal of Middle East Studies.

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn. Tafsir al-Mizan.

- Tabatabae, Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (1988). The Qur'an in Islam: Its Impact and Influence on the Life of Muslims. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-0266-3.

- Wild, Stefan (1996). The Quʼran as Text. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09300-3.

Further reading

- Recent translations

Main article: List of translations of the Quran#English

- Khalidi, Tarif (2009). The Qur'an: A New Translation. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-310588-6.

- Introductory texts

- Robinson, Neal, Discovering the Qur'an, Georgetown University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-1-58901-024-6

- Sells, Michael, – Approaching the Qur'ān: The Early Revelations, White Cloud Press, Book & CD edition (November 15, 1999). ISBN 978-1-883991-26-5

- Bell, Richard; William Montgomery Watt (1970). Bell's introduction to the Qurʼān. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0597-2.

- Rahman, Fazlur (2009) [1989]. Major Themes of the Qur'an (Second ed.). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70286-5.

- Traditional Quranic commentaries (tafsir)

Main article: List of tafsir

- Al-Tabari, Jamiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwil al-Qurʾān, Cairo 1955–69, transl. J. Cooper (ed.), The Commentary on the Qurʾān, Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-19-920142-6

- Topical studies

- Stowasser, Barbara Freyer – Women in the Qur'an, Traditions, and Interpretation, Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (June 1, 1996), ISBN 978-0-19-511148-4

- Gibson, Dan (2011). Qur’anic Geography: A Survey and Evaluation of the Geographical References in the Qur’an with Suggested Solutions for Various Problems and Issues. Independent Scholars Press, Canada. ISBN 978-0-9733642-8-6.

- McAuliffe, Jane Dammen (1991). Qurʼānic Christians : an analysis of classical and modern exegesis. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36470-6.

- Literary criticism

- Al-Azami, M. M. – The History of the Qurʾānic Text from Revelation to Compilation, UK Islamic Academy: Leicester 2003.

- Gunter Luling A challenge to Islam for reformation: the rediscovery and reliable reconstruction of a comprehensive pre-Islamic Christian hymnal hidden in the Koran under earliest Islamic reinterpretations. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers 2003. (580 Seiten, lieferbar per Seepost). ISBN 978-81-208-1952-8

- Luxenberg, Christoph (2004) – The Syro-Aramaic Reading Of The Koran: a contribution to the decoding of the language of the Koran, Berlin, Verlag Hans Schiler, 1 May 2007 ISBN 978-3-89930-088-8

- Puin, Gerd R. – "Observations on Early Quran Manuscripts in Sana'a," in The Qurʾan as Text, ed. Stefan Wild,, E. J. Brill 1996, pp. 107–111.

- Wansbrough, John – Quranic Studies, Oxford University Press, 1977

- Encyclopedias

- Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an. Jane Dammen McAuliffe et al. (eds.) (1st ed.). Brill Academic Publishers. 2001–2006. ISBN 978-90-04-11465-4.

- The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Oliver Leaman et al. (eds.) (1st ed.). Routledge. 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-77529-8.

- Encyclopedia of the Holy Qurʼân. A. R. Agwan and N.K. Singh (eds.) (1st ed.). Delhi: Global Vision Publishing House. 2000–2006. ISBN 978-81-87746-00-3.

- Academic journals

- Journal of Qur'anic Studies / Majallat al-dirāsāt al-Qurʹānīyah. School of Oriental and African Studies. 1999–present. ISSN 1465-3591.

- Journal of Qur'anic Research and Studies. Medina, Saudi Arabia: King Fahd Qur'an Printing Complex. 2006-present. http://jqrs.qurancomplex.gov.sa/en/.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Introduction

Islamic philosophy refers to philosophy produced in an Islamic society. It is not necessarily concerned with religious issues, nor exclusively produced by Muslims. [Oliver Leaman, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy][edit] Formative influences

Islamic philosophy as the name implies refers to philosophical activity within the Islamic milieu. The main sources of classical or early Islamic philosophy are the religion of Islam itself (especially ideas derived and interpreted from the Quran), Greek philosophy which the early Muslims inherited as a result of conquests when Alexandria, Syria and Jundishapur came under Muslim rule, along with pre-Islamic Indian philosophy and Iranian philosophy. Many of the early philosophical debates centered around reconciling religion and reason, the latter exemplified by Greek philosophy. One aspect which stands out in Islamic philosophy is that, the philosophy in Islam travels wide but comes back to conform it with the Quran and Sunna.[edit] Early Islamic philosophy

An Arabic manuscript from the 13th century depicting Socrates (Soqrāt) in discussion with his pupils.

[edit] Kalam

Main article: Kalam

Kalām (Arabic: علم الكلام) is the philosophy that seeks Islamic theological principles through dialectic. In Arabic the word literally means "speech". One of first debates was that between partisan of the Qadar (Arabic: qadara, to have power), who affirmed free will, and the Jabarites (jabar, force, constraint), who believed in fatalism.At the second century of the Hijra, a new movement arose in the theological school of Basra, Iraq. A pupil, Wasil ibn Ata, who was expelled from the school because his answers were contrary to then sunni tradition and became leader of a new school, and systematized the radical opinions of preceding sects, particularly those of the Qadarites and Jabarites. This new school was called Mutazilite (from i'tazala, to separate oneself).

The Mutazilites, compelled to defend their principles against the sunni Islam of their day, looked for support in philosophy, and are one of the first to pursue a rational theology called Ilm-al-Kalam (Scholastic theology); those professing it were called Mutakallamin. This appellation became the common name for all seeking philosophical demonstration in confirmation of religious principles. But subsequent generations were to large extent critical towards the Mutazilite school, especially after formation of the Asharite concepts.

More simply put Kalam means duties of the heart as opposed to (or in conjunction with) fikh duties of the body. Theology verses jurisprudence.[2]

[edit] Falsafa

Falsafa is a Greek loanword meaning "philosophy". "Science" is the Latin word for "philosophy".[edit] Divisions of the Philosophic Sciences

These sciences, in relation to the aim we have set before us, may be divided into six, sections:[3](1) Mathematics

(2) Logic

(3) Physics (The object of this science is the study of the bodies which compose the universe: the sky and the stars, and, here below, simple elements such as air, earth, water, fire, and compound bodies animals, plants, and minerals; the reasons of their changes, developments, and intermixture.) also includes medicine.

(4) Metaphysics

(5) Politics

(6) Moral Philosophy (ethics)

From the ninth century onward, owing to Caliph al-Ma'mun and his successor, Greek philosophy was introduced among the Arabs, and the Peripatetic school began to find able representatives among them; such were Al-Kindi, Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina (Avicenna), and Ibn Rushd (Averroës), all of whose fundamental principles were considered as criticized by the Mutakallamin. Another trend, represented by the Brethren of Purity, used Aristotelian language to expound a fundamentally Neoplatonic and Neopythagorean world view.

During the Abbasid caliphate a number of thinkers and scientists, some of them heterodox Muslims or non-Muslims, played a role in transmitting Greek, Hindu, and other pre-Islamic knowledge to the Christian West. They contributed to making Aristotle known in Christian Europe. Three speculative thinkers, al-Farabi, Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and al-Kindi, combined Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism with other ideas introduced through Islam.

From Spain Arabic philosophic literature was translated into Hebrew and Latin, contributing to the development of modern European philosophy.

[edit] Some differences between Kalam and Falsafa